This article on matrix inverses and determinants is part four of an ongoing crash course on programming with linear algebra, demonstrating concepts and implementations in Python. The inverse of a matrix and the determinant are fundamental concepts that reveal important properties about matrices and provide alternative methods for solving systems of linear equations.

Linear Algebra: Python Series - View all articles in this series.

Previous articles in this series:

This series began with Linear Algebra: Vectors, continued with Linear Algebra: Matrices 1, and most recently covered Systems of Linear Equations.

Python examples in this article make use of the Numpy library. Read the article Python Data Essentials - Numpy if you want a quick overview of this important Python library.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

The Matrix Inverse

The inverse of a square matrix $\boldsymbol{A}$, denoted $\boldsymbol{A}^{-1}$, is a matrix such that:

Where $\boldsymbol{I}$ is the identity matrix. Not all matrices have inverses; those that do are called invertible or nonsingular.

Computing the Inverse with NumPy

# Define a 2x2 matrix

A = np.array([[4, 7],

[2, 6]])

# Compute the inverse

A_inv = np.linalg.inv(A)

print(f"Matrix A:\n{A}\n")

print(f"Inverse A^(-1):\n{A_inv}\n")

Matrix A:

[[4 7]

[2 6]]

Inverse A^(-1):

[[ 0.6 -0.7]

[-0.2 0.4]]

# Verify: A @ A^(-1) = I

product = A @ A_inv

print(f"A @ A^(-1):\n{product}\n")

# Check if it's close to identity

identity = np.eye(2)

print(f"Is A @ A^(-1) = I? {np.allclose(product, identity)}")

A @ A^(-1):

[[1. 0.]

[0. 1.]]

Is A @ A^(-1) = I? True

Inverse of a 2x2 Matrix

For a 2x2 matrix, the inverse has a closed-form formula:

The term $ad - bc$ is the determinant of the matrix (more on this below).

def inverse_2x2(A):

"""Compute the inverse of a 2x2 matrix manually."""

a, b = A[0, 0], A[0, 1]

c, d = A[1, 0], A[1, 1]

det = a*d - b*c

if det == 0:

raise ValueError("Matrix is singular (non-invertible)")

return np.array([[d, -b],

[-c, a]]) / det

# Test the function

A_inv_manual = inverse_2x2(A)

print(f"Manual inverse:\n{A_inv_manual}\n")

print(f"NumPy inverse:\n{A_inv}\n")

print(f"Results match: {np.allclose(A_inv_manual, A_inv)}")

Manual inverse:

[[ 0.6 -0.7]

[-0.2 0.4]]

NumPy inverse:

[[ 0.6 -0.7]

[-0.2 0.4]]

Results match: True

Solving Systems Using the Inverse

If $\boldsymbol{A}\vec{x} = \vec{b}$ and $\boldsymbol{A}$ is invertible, then:

# Solve: 4x + 7y = 22

# 2x + 6y = 14

b = np.array([22, 14])

# Method 1: Using the inverse

x_inverse = A_inv @ b

print(f"Solution using inverse: {x_inverse}")

# Method 2: Using np.linalg.solve (more efficient)

x_solve = np.linalg.solve(A, b)

print(f"Solution using solve: {x_solve}")

# Verify

print(f"A @ x = {A @ x_inverse}")

Solution using inverse: [1. 2.]

Solution using solve: [1. 2.]

A @ x = [18. 14.]

Note: While using the inverse works, np.linalg.solve() is preferred for numerical stability and efficiency. Computing the inverse requires more operations and can introduce numerical errors.

The Determinant

The determinant is a scalar value computed from a square matrix. It encodes important information about the matrix:

- If $\det(\boldsymbol{A}) = 0$, the matrix is singular (non-invertible)

- If $\det(\boldsymbol{A}) \neq 0$, the matrix is invertible

- The absolute value of the determinant represents the scaling factor of the linear transformation

Determinant of a 2x2 Matrix

# Compute determinant using NumPy

det_A = np.linalg.det(A)

print(f"Matrix A:\n{A}\n")

print(f"Determinant: {det_A}")

# Manual calculation for 2x2

det_manual = A[0,0]*A[1,1] - A[0,1]*A[1,0]

print(f"Manual calculation: {det_manual}")

Matrix A:

[[4 7]

[2 6]]

Determinant: 10.000000000000002

Manual calculation: 10

Determinant of a 3x3 Matrix

For a 3x3 matrix, the determinant can be computed using cofactor expansion:

B = np.array([[1, 2, 3],

[4, 5, 6],

[7, 8, 9]])

det_B = np.linalg.det(B)

print(f"Matrix B:\n{B}\n")

print(f"Determinant: {det_B:.10f}")

Matrix B:

[[1 2 3]

[4 5 6]

[7 8 9]]

Determinant: 0.0000000000

Notice the determinant is essentially zero (numerical precision aside). This means the matrix is singular and cannot be inverted. Let’s verify:

# Check the rank

print(f"Rank of B: {np.linalg.matrix_rank(B)}")

print(f"Matrix B is {'singular' if np.isclose(det_B, 0) else 'invertible'}")

# The rows are linearly dependent: row3 = 2*row2 - row1

print(f"\nRow 3: {B[2]}")

print(f"2*Row2 - Row1: {2*B[1] - B[0]}")

Rank of B: 2

Matrix B is singular

Row 3: [7 8 9]

2*Row2 - Row1: [7 8 9]

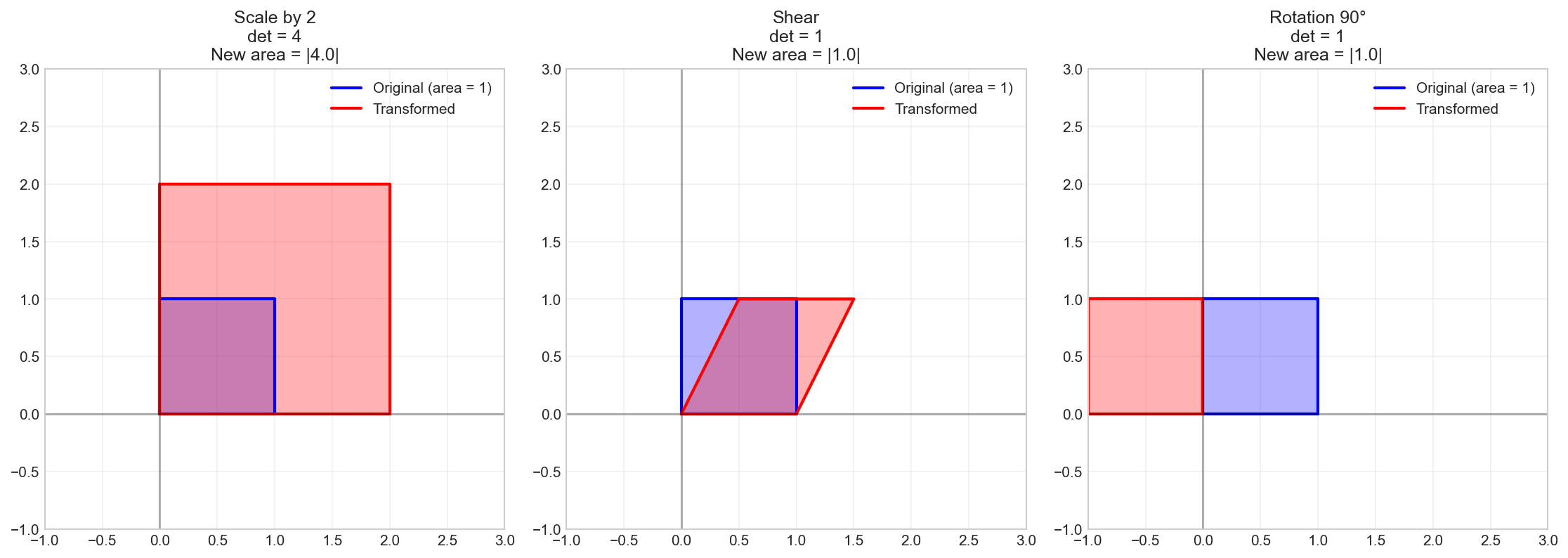

Geometric Interpretation of the Determinant

The determinant represents how the linear transformation scales areas (in 2D) or volumes (in 3D).

# Visualize the determinant as area scaling

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(15, 5))

# Original unit square

unit_square = np.array([[0, 0], [1, 0], [1, 1], [0, 1], [0, 0]]).T

# Three different transformations

transforms = [

np.array([[2, 0], [0, 2]]), # Scale by 2

np.array([[1, 0.5], [0, 1]]), # Shear

np.array([[0, -1], [1, 0]]) # Rotation 90 degrees

]

titles = ['Scale by 2\ndet = 4', 'Shear\ndet = 1', 'Rotation 90°\ndet = 1']

for ax, T, title in zip(axes, transforms, titles):

# Plot original unit square

ax.plot(unit_square[0], unit_square[1], 'b-', linewidth=2,

label='Original (area = 1)')

ax.fill(unit_square[0], unit_square[1], alpha=0.3, color='blue')

# Transform the square

transformed = T @ unit_square

ax.plot(transformed[0], transformed[1], 'r-', linewidth=2,

label=f'Transformed')

ax.fill(transformed[0], transformed[1], alpha=0.3, color='red')

det = np.linalg.det(T)

ax.set_title(f'{title}\nNew area = |{det:.1f}|')

ax.set_xlim(-1, 3)

ax.set_ylim(-1, 3)

ax.set_aspect('equal')

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax.legend()

ax.axhline(y=0, color='k', linestyle='-', alpha=0.3)

ax.axvline(x=0, color='k', linestyle='-', alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Properties of Determinants

Determinants have several important properties:

# Create two invertible matrices

A = np.array([[3, 1], [2, 4]])

B = np.array([[1, 2], [3, 1]])

det_A = np.linalg.det(A)

det_B = np.linalg.det(B)

print(f"det(A) = {det_A:.4f}")

print(f"det(B) = {det_B:.4f}")

det(A) = 10.0000

det(B) = -5.0000

Property 1: det(AB) = det(A) * det(B)

det_AB = np.linalg.det(A @ B)

print(f"det(AB) = {det_AB:.4f}")

print(f"det(A) * det(B) = {det_A * det_B:.4f}")

print(f"Equal: {np.isclose(det_AB, det_A * det_B)}")

det(AB) = -50.0000

det(A) * det(B) = -50.0000

Equal: True

Property 2: det(A^T) = det(A)

det_AT = np.linalg.det(A.T)

print(f"det(A^T) = {det_AT:.4f}")

print(f"det(A) = {det_A:.4f}")

print(f"Equal: {np.isclose(det_AT, det_A)}")

det(A^T) = 10.0000

det(A) = 10.0000

Equal: True

Property 3: det(A^(-1)) = 1/det(A)

A_inv = np.linalg.inv(A)

det_A_inv = np.linalg.det(A_inv)

print(f"det(A^(-1)) = {det_A_inv:.4f}")

print(f"1/det(A) = {1/det_A:.4f}")

print(f"Equal: {np.isclose(det_A_inv, 1/det_A)}")

det(A^(-1)) = 0.1000

1/det(A) = 0.1000

Equal: True

Property 4: det(cA) = c^n * det(A) for n x n matrix

c = 3

n = 2 # 2x2 matrix

det_cA = np.linalg.det(c * A)

print(f"det({c}A) = {det_cA:.4f}")

print(f"{c}^{n} * det(A) = {(c**n) * det_A:.4f}")

print(f"Equal: {np.isclose(det_cA, (c**n) * det_A)}")

det(3A) = 90.0000

3^2 * det(A) = 90.0000

Equal: True

Cramer’s Rule

Cramer’s Rule provides an explicit formula for solving systems of linear equations using determinants. For a system $\boldsymbol{A}\vec{x} = \vec{b}$:

Where $\boldsymbol{A}_i$ is the matrix $\boldsymbol{A}$ with its $i$-th column replaced by $\vec{b}$.

def cramers_rule(A, b):

"""Solve Ax = b using Cramer's Rule."""

det_A = np.linalg.det(A)

if np.isclose(det_A, 0):

raise ValueError("Matrix is singular; Cramer's Rule not applicable")

n = len(b)

x = np.zeros(n)

for i in range(n):

A_i = A.copy()

A_i[:, i] = b # Replace i-th column with b

x[i] = np.linalg.det(A_i) / det_A

return x

# Solve the system:

# 3x + y = 9

# 2x + 4y = 14

A = np.array([[3, 1],

[2, 4]])

b = np.array([9, 14])

# Using Cramer's Rule

x_cramer = cramers_rule(A, b)

print(f"Cramer's Rule solution: {x_cramer}")

# Verify with np.linalg.solve

x_solve = np.linalg.solve(A, b)

print(f"np.linalg.solve: {x_solve}")

Cramer's Rule solution: [2. 3.]

np.linalg.solve: [2. 3.]

Note: While Cramer’s Rule is elegant, it’s computationally expensive for large systems. It’s mainly useful for theoretical analysis and small systems.

Properties of Invertible Matrices

A square matrix $\boldsymbol{A}$ is invertible if and only if:

- $\det(\boldsymbol{A}) \neq 0$

- $\boldsymbol{A}$ has full rank ($rank(\boldsymbol{A}) = n$)

- The columns (or rows) of $\boldsymbol{A}$ are linearly independent

- The system $\boldsymbol{A}\vec{x} = \vec{b}$ has exactly one solution for every $\vec{b}$

- The null space of $\boldsymbol{A}$ contains only the zero vector

# Check various properties for an invertible matrix

C = np.array([[1, 2, 3],

[0, 1, 4],

[5, 6, 0]])

print(f"Matrix C:\n{C}\n")

print(f"Determinant: {np.linalg.det(C):.4f}")

print(f"Rank: {np.linalg.matrix_rank(C)}")

print(f"Is invertible: {not np.isclose(np.linalg.det(C), 0)}")

Matrix C:

[[1 2 3]

[0 1 4]

[5 6 0]]

Determinant: 1.0000

Rank: 3

Is invertible: True

# Compute and display the inverse

C_inv = np.linalg.inv(C)

print(f"Inverse of C:\n{C_inv}\n")

# Verify

print(f"C @ C^(-1):\n{np.round(C @ C_inv, 10)}")

Inverse of C:

[[-24. 18. 5.]

[ 20. -15. -4.]

[ -5. 4. 1.]]

C @ C^(-1):

[[1. 0. 0.]

[0. 1. 0.]

[0. 0. 1.]]

Numerical Considerations

When working with matrix inverses and determinants in practice, numerical precision matters:

# Create a nearly singular matrix

D = np.array([[1, 2],

[1.0001, 2.0002]])

det_D = np.linalg.det(D)

print(f"Matrix D:\n{D}\n")

print(f"Determinant: {det_D}")

print(f"Condition number: {np.linalg.cond(D):.2f}")

Matrix D:

[[1. 2. ]

[1.0001 2.0002]]

Determinant: 1.9999999899641377e-08

Condition number: 60003750.03

The condition number indicates how sensitive the solution is to small changes in the input. A large condition number suggests the matrix is ill-conditioned.

# Solving with an ill-conditioned matrix can give unreliable results

b1 = np.array([3, 3.0003])

b2 = np.array([3, 3.0004]) # Small change in b

x1 = np.linalg.solve(D, b1)

x2 = np.linalg.solve(D, b2)

print(f"Solution for b1: {x1}")

print(f"Solution for b2: {x2}")

print(f"Change in b: {np.linalg.norm(b2 - b1):.6f}")

print(f"Change in x: {np.linalg.norm(x2 - x1):.2f}")

Solution for b1: [1. 1.]

Solution for b2: [-3999. 2001.]

Change in b: 0.000100

Change in x: 5000.00

Summary

In this article, we covered:

- Matrix inverse: $\boldsymbol{A}^{-1}$ such that $\boldsymbol{A}\boldsymbol{A}^{-1} = \boldsymbol{I}$

- Computing inverses with

np.linalg.inv() - Determinants and their geometric interpretation as scaling factors

- Properties of determinants: multiplicative, transpose invariance, etc.

- Cramer’s Rule for solving systems using determinants

- Invertibility conditions and their equivalence

- Numerical considerations for ill-conditioned matrices

Resources

- Matrix Inverse - Khan Academy

- Determinants - Khan Academy

- NumPy Linear Algebra

- Condition Number - Wikipedia

Next: Vector Spaces and Subspaces

Check out the next article in this series, Linear Algebra: Vector Spaces and Subspaces.

Linear Algebra: Python Series - View all articles in this series.

This blog post, titled: "Linear Algebra: Matrix Inverses and Determinants: Linear Algebra Crash Course for Programmers Part 4" by Craig Johnston, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.